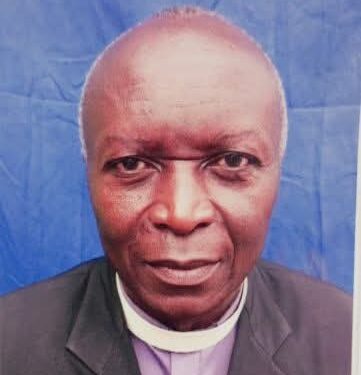

Sheikh Shaban Ramadhan Mubaje has been re-elected as the Mufti of Uganda under the Uganda Muslim Supreme Council (UMSC), a decision that has reignited tensions within the Muslim community and drawn sharp criticism over constitutional compliance. Mubaje, who turned 70, yesterday, March 12, 2025, secured another term in a closely watched process, just hours before his mandated retirement age under the UMSC’s legal framework was set to take effect.

The re-election comes against a complex backdrop of constitutional interpretation and legal disputes. Mubaje was first elected Mufti on December 11, 2000, under the UMSC constitution as amended in 1987, which stipulated that the Mufti remains in office until reaching 70 years of age. Having served over 24 years, he reached that threshold yesterday, a milestone that many expected would mark the end of his tenure. However, the UMSC constitution, amended in 2022, introduced transitional provisions under Article 29(12), stating that those in office at the time of enactment—July 13, 2022—must complete their tenure without automatic extension unless re-elected under the new rules.

The 2022 amendments raised the retirement age for the Mufti to 75 and set a term limit of one renewable 10-year term, alongside stricter qualifications, including a master’s degree in Sharia or its equivalent. Supporters of Mubaje’s re-election argue that Article 29(12) allowed him to seek another term, citing his leadership achievements—such as strengthening UMSC’s institutional framework and fostering interfaith dialogue through the Inter-Religious Council of Uganda—as justification for his continued tenure. The College of Eminent Sheikhs, now tasked with electing the Mufti under the amended constitution, affirmed his re-election in a closed-door session, with officials stating that Mubaje’s experience remains vital amid ongoing factionalism within Uganda’s Muslim community.

Yet, the decision has sparked outrage and legal pushback. A group of Sunni Muslims, including Swaibu Nsimbe, Twayibu Byansi, Musa Kalokora, and Musa Kasakya, filed a judicial review application at the High Court in Kampala days before the election, seeking to declare Mubaje ineligible. They argued that Article 29(12) does not grant an automatic extension and that his 24-year tenure exceeds the 10-year limit introduced in 2022, rendering his candidacy invalid. “The failure to vacate the office by midnight on March 12 violates the constitution and principles of good governance,” Kasakya stated in an affidavit, urging the court to nullify the re-election and order a new process.

The petitioners’ case, still pending as of Thursday afternoon, also questions Mubaje’s qualifications. While he holds a bachelor’s degree in Sharia from Saudi Arabia and a master’s in religious studies from Makerere University, critics contend that the latter does not meet the 2022 requirement for a Sharia-specific master’s degree. UMSC spokesperson Ashraf Zziwa Muvawala dismissed these claims, asserting that Mubaje’s credentials are sufficient and that the court challenge is a “recycled tactic” by detractors. “We’ll meet them in court and trust the process,” Zziwa said.

Mubaje’s leadership has long been polarizing. His 24-year reign has seen UMSC grow as a government-recognized body, managing vast properties and educational initiatives, but it has also been marred by accusations of mismanagement and power consolidation. The sale of Muslim properties, including a controversial deal in Sembabule that led to a Shs19 billion debt, has fueled dissent, with rival factions like the Kibuli-based group under Supreme Mufti Muhammad Galabuzi gaining traction. Wednesday’s re-election has deepened these divides, with some community members accusing the College of Sheikhs of rubber-stamping Mubaje’s bid to cling to power.

The timing of the re-election—coinciding with Mubaje’s 70th birthday—added a layer of drama. Supporters gathered at the UMSC headquarters in Old Kampala to celebrate, hailing his resilience and vision. “Sheikh Mubaje has united us where others failed,” one attendee remarked. Critics, however, saw it as a defiance of constitutional intent. “This is a mockery of the law and the Muslim faithful,” a dissenting Sheikh commented anonymously, citing fears of unrest.

As Mubaje begins his new term, the High Court’s ruling could yet upend his victory. Legal experts suggest that if the court sides with the petitioners, it might not only void the re-election but also force UMSC to overhaul its electoral process. For now, Mubaje remains at the helm, his swearing-in scheduled for later this week barring judicial intervention. With Uganda’s Muslim community watching closely, the outcome of this saga could redefine the UMSC’s leadership and its role in a nation grappling with religious and political fault lines.