Raising a child today is a mix of deep joy and constant worry. Every new step brings excitement, but it also brings new fears.

Parents wait eagerly for a child to crawl or walk. When it happens, the celebration is short. Soon after, cups fall, plates break and nothing fragile feels safe. A child will spill food, scatter toys and test patience daily. In those moments, parents must remind themselves that children are still learning. They do not know better.

Childbirth itself is a powerful and beautiful experience. Children come into the world innocent and curious. They are honest in ways adults are not. They do not pretend. They do not hide emotions. They act on feeling, not reason.

Psychologists explain this by saying children act mainly on desire and comfort. They do not yet understand empathy or responsibility. That is why young children can appear selfish, rude or even biased. Their innocence does not mean they are faultless. It means they do not yet understand the harm their actions can cause.

The cost of raising a child is another reality many parents avoid talking about. It is emotionally painful to calculate how much has been spent and how much more lies ahead. Despite careful planning, expenses remain high.

In our home, my child will turn one year old on Jan. 4, 2026. So far, both parents have been present, but the truth is clear. The mother does most of the work. Fathers often convince themselves they are doing enough, especially after returning home tired from work.

Recently, a colleague, Atwine (not real name), a first-time mother, shared her experience. After her child broke nearly all the ceramic plates in her house, she replaced them with plastic ones. Her story felt familiar. My own child started walking on Dec. 28, 2025, shortly after we returned from our village in Kikonkoma, Rwampara District, where we spent Christmas with family. I know similar destruction is coming.

But behind these everyday struggles is a darker fear. About a year ago, another colleague, Bamwine, lost her eight-month-old son while he was under the care of a housemaid. At first, the death was blamed on a fall from a sofa. Many parents doubted this explanation, saying their own children had fallen from beds and chairs without serious injury.

Later, the housemaid confessed. She had suffocated the child after becoming angry with the mother, who returned home at lunchtime and found no food prepared. The story remains a painful reminder of the risks working parents face when they must leave children in the care of others.

This is why workplaces must change.

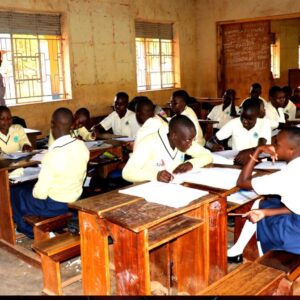

A few months ago, I visited the Institute (formerly college) of Women and Gender Studies at Makerere University. I was impressed to find a fully established baby care center. It showed what is possible when institutions take parenting seriously.

Workplaces should be more friendly to parents, especially mothers. Baby care facilities at work are not charity. They are an investment. Parents who feel safe about their children work better. They are more focused, loyal and productive.

Governments and public institutions should lead by example. Strong maternity and paternity policies benefit everyone. Family-friendly workplaces do not weaken organizations. They strengthen them.

A workforce under stress cannot perform at its best. A supported workforce becomes more creative, committed and productive.

Society is slowly drifting toward systems that are hostile to family life. This trend is dangerous. It threatens the future of humanity itself.

Governments, religious institutions and employers must work together to protect families. Laws and policies should support parenting, not punish it. When families are supported, society survives.