A new global study has found that most popular virtual private networks, or VPNs, do not route internet traffic through the countries they claim, raising fresh questions about trust, transparency and digital safety.

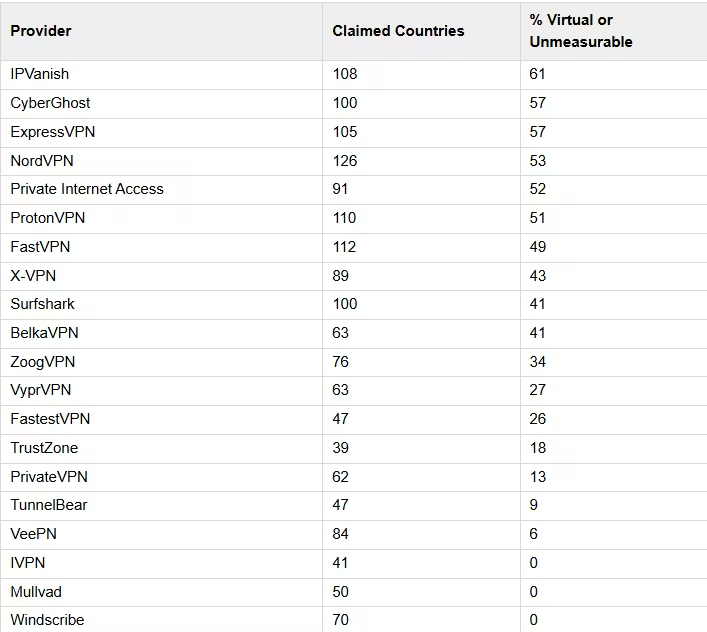

The study, conducted by IP data firm IPinfo, analyzed 20 widely used VPN providers and found that 17 of them routed traffic through countries different from those advertised to users. Some VPNs claim to offer servers in more than 100 countries, but many of those locations were found to exist only on paper.

Instead, traffic often exited from a small number of physical data centers, mainly in the United States and Europe.

For Ugandans, the findings come at a time when VPN use is rising, especially among journalists, activists, businesspeople and young internet users who often try to hide their online identity due to surveillance fears, political pressure or social stigma.

Table of Contents:

What the Study Found

IPinfo examined more than 150,000 VPN exit IP addresses across 137 possible countries. Using live internet measurements, the researchers compared what VPN providers claim with where traffic actually exits.

Their findings include:

-

17 out of 20 VPN providers routed traffic through a country different from the one shown to users.

-

38 countries were listed by VPNs but never appeared as real exit locations.

-

Only three providers — Mullvad, IVPN and Windscribe — matched all their advertised locations.

-

About 8,000 cases showed IP location data placing servers in the wrong country, sometimes thousands of kilometers away.

The study used IPinfo’s ProbeNet system, which runs live tests from more than 1,200 locations worldwide to measure where internet traffic physically exits.

Virtual Locations, Real Concerns

Many VPNs use what are known as virtual locations. This means a user may select a country such as the Bahamas or Somalia, but their internet traffic actually passes through servers in places like the United States, France or the United Kingdom.

In most cases, both the VPN app and public IP records show the same country label, even when the traffic is physically somewhere else. That is because many IP databases rely on information self-declared by the server owner, rather than live measurement.

Without active testing, errors can spread across the internet and remain undetected.

Case Studies: Countries That Exist Only on VPN Maps

The study highlighted several examples where VPN locations existed only in name.

In the Bahamas, five major VPN providers claimed to offer servers. However, all measured traffic exited from the United States, often with near-zero delay, indicating physical proximity to U.S. servers.

In Somalia, two providers labeled servers as “Mogadishu,” but network measurements showed the traffic actually exited from France and the United Kingdom. The delay times were consistent with Western Europe, not East Africa.

Why This Matters in Uganda

In Uganda, VPNs are widely used during elections, protests and periods of political tension. Many users rely on VPNs to hide their identity, avoid online tracking or access restricted content.

Journalists, civil society groups and opposition supporters often choose VPN locations based on perceived safety. A server labeled “Somalia” may be assumed to carry different risks from one in France or Britain.

“If both the VPN and IP data say one thing, but the traffic is actually somewhere else, decisions are being made on false information,” the report said.

This is especially important in countries like Uganda, where online activity can have real-world consequences, including arrests, job loss or intimidation.

Not All VPNs Are “Bad”

The researchers stressed that using virtual locations does not automatically mean a VPN is unsafe or dishonest.

There are practical reasons for avoiding physical servers in some countries, including:

-

Weak internet infrastructure

-

High operating costs

-

Risk of government seizure or surveillance

-

Poor data center availability

Serving regional traffic from stable hubs like London, Amsterdam or Miami can improve speed and reliability.

However, the issue becomes one of trust when providers do not clearly disclose which locations are virtual.

When Transparency Breaks Down

According to the report, trust problems arise when:

-

VPNs do not label virtual locations clearly

-

Dozens of countries exist only as names

-

Users rely on location claims for safety or legal reasons

For professionals such as journalists, NGOs and researchers, accurate location data is critical.

How IPinfo Verified the Data

IPinfo used live network tests to measure how long data took to travel between servers and global probes. In many cases, the delay was under one millisecond, a strong sign that the server was physically close.

By contrast, some IP databases placed the same servers thousands of kilometers away, with a median error of about 3,100 kilometers.

What VPN Users Should Know

The study advises users to be cautious when choosing a VPN based only on country count.

Key takeaways include:

-

Treat claims like “100+ countries” as marketing, not proof

-

Check whether virtual locations are clearly labeled

-

Understand that IP data accuracy varies widely

For Ugandans, especially those using VPNs for safety, the findings underline the importance of knowing not just what a VPN claims, but where traffic actually goes.

A Call for Evidence-Based Internet Data

IPinfo says its goal is not to attack VPNs, but to encourage honesty and verification.

“Trust should be backed by evidence,” the report said. “If a VPN shows a map of flags, users deserve to know whether those flags reflect real infrastructure or just labels.”

As more Ugandans turn to VPNs to protect their identity online, the gap between claims and reality is likely to attract even closer scrutiny.